This past weekend I went to the top of a mountain to hear an incredible story. Located on the Continental Divide, just east of Steamboat Springs, Colorado, is Buffalo Pass. At just shy of 11,000 feet, the atmosphere is thin and the view is breath taking. More so for a flat land Georgia boy like me. On December the fourth, 1978, the isolation of Buffalo Pass was shattered when a giant ice formation fell from the night sky and was buried in the snow. It was as if Aliens had invaded Earth when human forms began emerging from the snow bank and standing in the shaft of light emanating from whatever had fallen from the sky. However, there was no one anywhere near Buffalo Pass to observe the strange scene. Why would anyone in their right mind be out in a raging blizzard with snow accumulating by the foot and wind spilling over the mountain crest at 60 knots or more? Humans are not designed to function with wind chills at 50 below. Even the Elk and Bear that normally inhabited the forest had taken shelter elsewhere.

Thirty-eight years later, on an early October morning, I stand on Buffalo Pass enjoying a pleasant clear morning with the temperature in the fifties and a gentle breeze rustling through the forest. The weather forecast is for rain, but the prognosticators have somehow miscalculated. Only experienced aviators, of which I humbly include myself, understand the fickle nature of weather and the limited credibility of forecast. That is not to say I understand the weather. Only the fickle nature. Walking with me, as we climb over fallen trees and I stumble over rock formations, is another aviator. Gary Coleman is explaining the events of that night long ago when a Rocky Mountain Airways De-Havilland Twin Otter flew into a glacier like cloud and could not escape until the cloud decided to calve it off and force it down on Buffalo Pass. The ice was so thick, the smooth airfoils of the “Twotter” now resembled the rough peaks of the mountains below. The de-ice boots on the leading edge of the wings pulsed in vain as ice weighed the airplane down and destroyed the lift capability of the wings. It simply refused to climb and then refused to hold altitude. Gary Coleman occupied the copilot’s seat of Rocky Mountain Airways Flight 217.

Gary and I are accompanied by his lovely wife Debi and their faithful Yellow Lab, Miles. We have abaondoned the four wheel drive Suburban on a Forest Service Road, and now we travel the steep terrain on foot, hoping a hunter doesn’t mistake us for Elk. Debi is a former flight attendant and a pilot in her own rite. Our journey to the crash site is thwarted by a deep ravine, but we are determined and climb higher to find a way around the obstacle. I feel great anticipation at the possibility of reaching the crash site, and then I feel guilt as I realize Debi and Gary are experiencing different emotions. Miles ignores us and cavorts through the woods as if he owns the mountain.

There were twenty-two souls on board the airplane that night, and miraculously twenty-one of them not only survived the impact, but also refused to succumb to the inhuman environment of the blizzard until they were rescued the next day. First Officer Coleman and Captain Scotty Klopfenstein, never gave up and fought the airplane and the fickle weather until the very end. When the mountain wave of air spilling over the crest of Buffalo Pass forced the airplane down, the right wing clipped the tower of a high voltage power line, shearing off several feet of wing and the aileron. At the last second Gary kicked the right rudder to avoid a rock wall and slewed the airplane into a snow bank instead. A life-saving decision for twenty of the twenty-two souls on board. One passenger passed away on the mountain, and Captain Klopfenstein died a few days later in the hospital.

The wings sheared off and the fuselage rolled onto its right side as the machine, no longer an aircraft, came to a stop. The cockpit opened up and the windshield blew out before the skid ended. Snow scooped into the flight deck and left Gary trapped and buried up to his chest. As the blizzard continued to howl, the accumulating snow covered him almost completely, leaving only his hands to indicate a human was still there. Gary would need fate, fortune, or divine intervention to survive, and whether it was circumstance, luck, or divinity, help arrived in the form of a twenty year old passenger named Jon Pratt. Jon, an Eagle Scout and trained in survival skills, found Gary and removed the snow covering his face, allowing him to breathe. Gary was later diagnosed with a ruptured spleen, a concussion, numerous lacerations, and eventually frostbite. He could not be extracated from the cockpit until the next day. Somehow the ship’s battery continued to power the cabin lights and also the same ice lights on the exterior of the fuselage that had allowed Gary to watch the ice build on the wings. The ice lights evidently gave Jon the opportunity to discover Gary and render aid.

Meanwhile, elements of the Civil Air Patrol, Rocky Mountain Rescue, Sheriffs Deputies, and scores of local volunteers organized to search and rescue. Following the erratic signal of the aircraft’s Emergency Locator Tramsmitter, they were able to navigate as far as the Grizzly Creek Ranger Station below Buffalo Pass before the road became impassable. Now, Snow Cats and Ski Mobiles were the only way to move higher up the mountain. Tough, courageous men did just that and radioed back at six a.m. that survivors, including Gary Coleman, had been found. Evacuation began and the passengers and crew were transported down the mountain to the ranger station where they were triaged and moved to several local hospitals in ambulances with rattling snow chains on the tires. The ranger station consisted only of a tiny cabin with a pot bellied stove, but it was a luxury resort on that night.

Now, on this warm October morning, we stand at the base of the tower the airplane first impacted. We silently imagine the Twin Otter buried in snow with its lights still illuminated. I am so impressed with the courage and determination of Gary Coleman. Just the kind of aviator I always enjoyed flying with. He points out the direction of approach and where the airplane came to rest.

It has been thirty-seven years since he last visited the crash site, shortly after the accident. I wander away in order to allow he and Debi some privacy to process together. Miles ignores all of us.

Debi reaches down and picks up an object from the ground. It is a piece of the fiberglass bulkhead from the Otter’s baggage compartment. We find more debris among the rocks and grass including an aircraft bonding strap designed to prevent static electricity from arcing between metal surfaces. Some of the small metal debris still features the blue paint of Rocky Mountain Airways. A testament to the endurance of polyurethane.

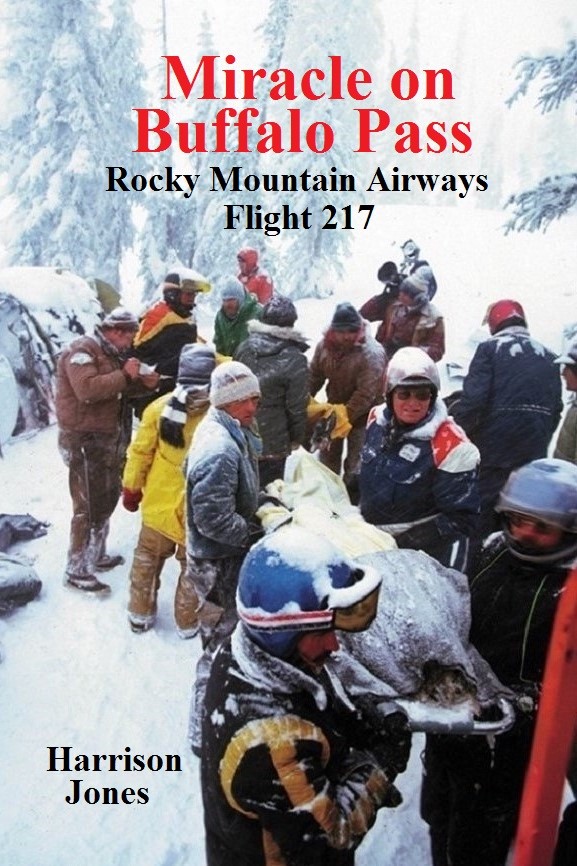

This story cannot be told in a blog post. It deserves to be told in a way that can be a legacy to all involved. The passengers, the crew, the search and rescue personell, the EMT’s, the doctors and nurses, and other volunteers who gave so generously. It needs to be told in their words from their perspective. It needs to serve as inspiration for others who are faced with adversity in their lives. It is testament that the human spirit can endure, and survive, and prosper. With the help of Gary, Debi, and their daughter Kelly, I intend to do just that in the form of a non-fiction book. The book is not yet titled, the first chapter is not written, and I am overwhelmed by the task at hand, but God willing, it will happen. Check back for progress reports.